Climate Change and the Slow Apocalypse

A world steeped in disaster and disruption is coming.

Thanks for bearing with me while I took a bye over the holidays. A moment away from all this was necessary, I think, and it’s important to recharge, relax, and remember what we’re supposed to be preserving. I wish that this post were some kind of retrospective on what we’ve beaten this year, or that it was something hopeful for our future, but it’s not. The whole point of this newsletter is to take the bad and tell you how to prepare for it—the hope comes in after that. Well, there’s a lot of bad coming. Today’s letter takes a broad-ish look at what we can expect in the near future. Briefly: 2020 is the floor of bad years, not the ceiling.

Facing Facts

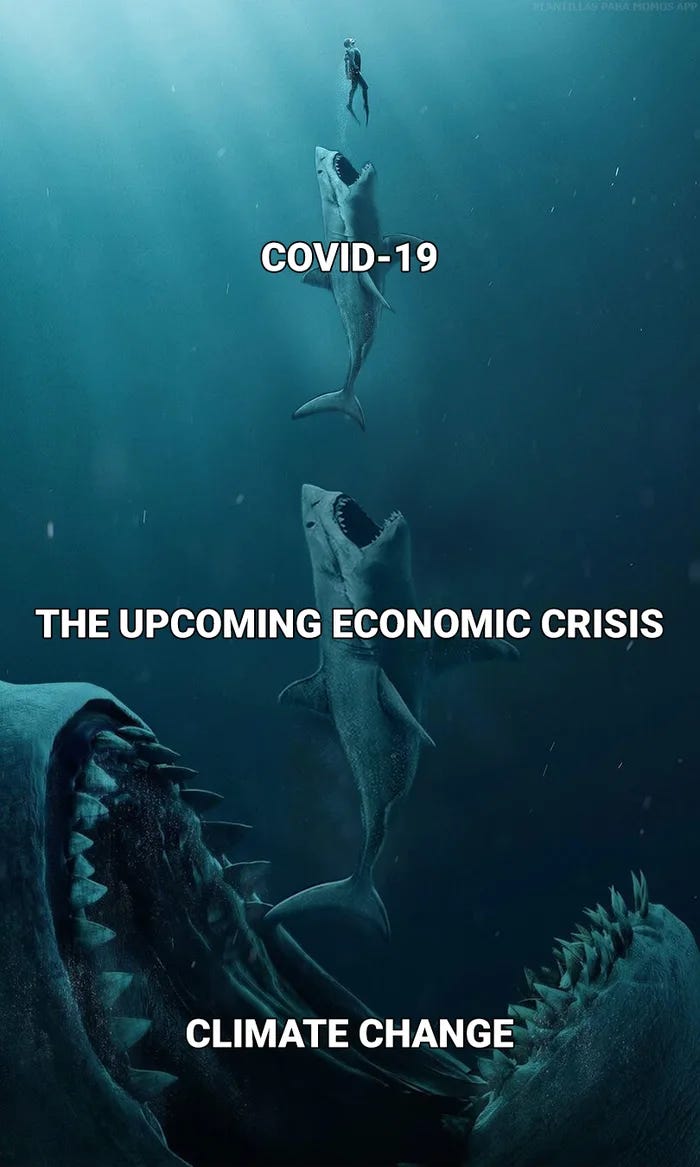

I've talked about climate change a fair bit over the course of this newsletter, but this week, looking at the past year and the year ahead, I want to drill down on it. Climate change is the existential threat of our species. Nothing—not COVID, not the threat of nuclear war, nor fascism—compares because ultimately climate change could engender all these things. It likely will.

Climate change is not an opportunity to invent our way out of destruction. It’s not an opportunity any more than a meteor hurtling toward the Earth is an opportunity to sell steel umbrellas.

There is no way that we will avert climate change. Most everyone who agrees climate change is real will also say that we can work to stop it—and insist that saying otherwise is a bad take. Well, we can’t stop it. I’m sure you’ve heard that there’s time, but not much. That there’s a chance, but a slim one. That’s true. Aliens could bestow upon us the gift of cold fusion and highly efficient carbon sequestration techniques. It’s a possibility, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

If we removed every roadblock, every Trump, every Mitch McConnell, every oil company, we would still have to essentially halt civilization as we know it in order to prevent catastrophic climate change—and I mean catastrophic. Terrible, horrible, no good, very bad climate change is locked in. We would need to remove every roadblock, halt civilization, and invent technology we don't exactly have in order to fully prevent climate change. This is why I say that climate change cannot be averted. It is a certainty. It’s already here.

We’re likely not going to stop worsening climate change, either. Realistically, we would need a mobilization effort that would dwarf WWII. It would be global, and it would involve an immediate end to fossil fuels. That transition would be chaotic at best, and ineffective at worst, depending on how immediate “immediate” is: on one end of the spectrum, we become a pre-industrialized civilization overnight—a disaster in its own right—and on the other, we scale down so slowly that we’re little better than current global efforts. And even if we were to concentrate our attention on climate change, COVID-19 has showed how ill-prepared the world, and America in particular, is to confront such a threat. The best option for progress logically lies between pulling out all the stops and the pie-eyed ideals of net-zero rhetoric, but we’re flensing Peter to pay Paul no matter what.

What is likely to happen is a movement that is somewhere north of Biden but south of a Green New Deal. To discount that amount of effort as worthless is incorrect, but to say that it’s adequate is malicious. Despite the dangers of pushing pause on civilization (which is a thought experiment—it’s never going to happen without a revolution, which, tag me if it does), in a way it’s our best option. What we’ll face due to inaction mirrors the pause scenario by virtue of disruption. We’ll see civilization halt in fits and starts, and despite that, we still won’t take the necessary steps. We’re going to poison our cake, and eat it, too.

In capitalism, disruption is an opportunity—a new product or service "disrupts" the market and replaces an old good or service, advancing the human race: thanks, capitalism! And many forward-thinking capitalists are looking to climate change as an opportunity. Here's the thing: it's not. It's not an opportunity any more than a meteor hurtling toward the Earth is an opportunity to sell steel umbrellas. Yeah, Elon’s gonna make a lot of electric cars, but that fact won’t save him from the fire. Don’t let anyone tell you different; this is not some opportunity to invent our way out of destruction. If we manage to avert disaster, it will not be because of human ingenuity. It will be because we toppled the rich and powerful who gilded their mansions while we were burning.

Disruption and the New Normal

The disruptions we will face are the traditional definition: an interruption of the status quo. COVID-19 gave us all a peek at disruption. For many, myself included, these disruptions were at times distant inconveniences, but for far too many more—and the brunt felt by people of color—jobs were lost, homes threatened, and food in short supply. Coming disruptions will be distant for an ever-dwindling few, and the impacts of climate change—even immediate ones—could result in widespread and long-term disruption.

We talk about emergencies constantly in this newsletter, but when it comes to these disruptions, I want you to think of them almost as the opposite: they are the new normal.

COVID-19 showed how brittle our supply chain can be. When quarantines in the spring led to the shutdown of restaurants across the country, billions of potatoes, for example, were uneaten and buried because the market is designed for expedience over resilience: restaurant-bound potatoes couldn’t go to grocery stores, so they were destroyed. This can easily happen again with another pandemic or another large-scale disaster.

Food in general is going to become more expensive, even when its flow is not disrupted. Anticipated losses to agricultural production are significant with a <2C rise in temperature—the amount of rise that is essentially locked in today. While some areas of the country and world will see an increase in productivity, much of our traditional breadbasket will have a hard row to hoe, with consistent difficulties as temperatures rise.

In recent years, California has seen large swaths of its population without power due to required power outages to prevent wildfires. Aging infrastructure and inherent risks due to heat and dry weather will expand these outages, and don’t expect California to be the only state affected. It’s important to remember that our electrical grid is linked across wide regions, and those systems power others. There are many reasons why a grid can fail, and climate change exacerbates a lot of them.

Water shortages are a major reason to stay up at night. Water is becoming more scarce across the nation as demand increases. A stark indicator of where we stand: water futures are now being traded on the stock market—generally not a thing for goods that are readily available. Water security is perhaps the most important of our necessities, and if history is any indicator, “water wars” won’t be between nations but between groups of economic interests, political alignments, and ethnic groups. If this doesn’t ring alarm bells for you, allow me to pull the rope: this is going to become a devastating chokepoint for eco-fascists.

Pandemics will become more frequent due to the expanded territories of disease-laden insects and the flight and adaptation of animals whose habitats we’ve destroyed. Recent headline-grabbers like Zika and the brain-eating amoeba are not one-offs; they’re going to become more prevalent and part of a crowd of other diseases. We’ve seen an increase in pandemics in general over the past 20 years, and that’s bound to continue.

These are all the human-facing side effects of climate change, the tipping dominoes that aren't always related to a specific drought or flood but instead related to the general conditions of a warming planet. We talk about emergencies constantly in this newsletter, but when it comes to these disruptions, I want you to think of them almost as the opposite: they are the new normal. They are the milieu in which the fires and floods and storms occur. These disruptions will come with an increasing frequency and severity until the very thing they are disrupting ceases to be.

The Slow Apocalypse Has Already Begun

I’ve been studying climate change as a layman for more than 10 years. Most of my fiction takes it as a core idea. My first novel came out in 2014, and a kind review referred to the conditions in it as the “slow apocalypse,” a gradual unraveling of society and the world we know. Even back then, I was worried that my work was being outpaced by reality, and that concern has been born out by the facts.

If you follow climate change closely for more than few years, you’ll find that each new report blows past the predictions of those that came before. Ten years ago, writing my book, I imagined a new Dust Bowl in 2030. We’re ripe for one today. I’ve watched the narrative shift from predicting disasters to seeing them around us. And I’ve watched, recently, as the narrative begins to shift from “climate change is here” to “we need to think about the collapse of society.”

Most science, and popular digestion of it, is focused on what’s to come by 2100 and other far-reaching effects of climate change. I’m talking about what we could see in our lifetimes, in the next decade, now. What we will see is less likely to be the full collapse of society than the drip-feed breakdown of all we used to know. We’ll see the disruption of services, of the supply chain, of routine. You’ll wake up one day to water rationing, no matter where you are in the country. You’ll wake up one day and wonder why your lights are off. You’ll wake up one day and get in line for bread.

I don’t say this to be alarmist or defeatist. Preparedness is not about either; it’s quite the opposite. I say this so that when the water supply is cut while your house is on fire, you’re not caught off guard. Surviving is going to depend upon expecting both—and more. Surviving is going to depend on you being able to get through all this without the help of society. The government, our politicians, and the market are not going to save us. They created this, and they are, the rich few of them, profiting from it still.

While I do not believe that we will head off climate change, I do believe that it is possible for us to live through it, and despite my disdain for the concept, take the opportunity to live in equilibrium with the planet. This is, however, the only option. We either adapt, or we die out. And we adapt—I mean you and me—by paying attention and getting ready now.

Preparing for the Slow Apocalypse

The slow apocalypse—I promise I’m not trying to coin a phrase, it’s just useful—is the gradual curtain-pull on the modern era. It’s the end of the conveniences and services that we’re used to amid the increased instability of the world around us; again, the milieu in which disasters will continue to occur, rather than one world-ending calamity.

Being truly prepared for everything that can come your way means we have to reckon with the real possibility that all the preps we’ve made up to this point are simply inadequate. I will readily tell you that while I’ve been building out my pantry and water supply, I’m not ready. I don’t have enough of either food or water, I don’t make enough of my own food, nor do I live in a place that’s particularly secure if things turned bad for a long time. But, despite my doom and gloom, that’s okay. Preparedness is a journey. So long as we’re walking in that direction, we’re probably better off than we were the day before. It’s important to recognize that.

There are two practical preps I want you to consider today. The first one involves researching your region’s likeliest disaster and creating a prep solely for that (I’ll walk you through some examples); the second is joining or starting a mutual aid network or pod in your area.

Prepping for a Local Disaster (or Go Columbus Floods!)

Here is a useful article for figuring out what you’re likely to be hit with. The Red Cross has a less impressive but more useful map as well. Once you’ve figured out your hometown’s disaster, find one actionable thing you can do to help mitigate the damage from it. Some examples include:

Flooding: If you live in a flood-prone area, you’d do well to locate emergency supplies up high. Many folks will naturally store these items in a basement, but if your property were to flood, those supplies might become unreachable or unusable quickly. At my hospital, I had to point out that keeping our emergency cache of water in an oft-flooded basement was a bad idea.

Thunderstorms: Whether tornadoes or derechos, find a secure central location in which you and your family might shelter. Put a weather radio and a small store of water and food there. A blanket or two wouldn’t hurt, either, if this is an uncomfortable location like an unfinished basement.

Fire: Prepare a go-bag with essential documents, photos, and medicine, and keep it near your door. Pair this with a bag or tote in your vehicle that has emergency rations and water in it at all times. Valuables that are too heavy to bring should be stored in a fire-proof safe.

Starting a Prepared Community

The single best way we prepare for the loss of what we know of as society is to recreate it in microcosm through mutual aid networks. Build a community of like-minded individuals and families that you can rely on. A community is important because no one is good at everything, and society as we know it now has specialized us into corners. With other people, you’re not stuck with one skillset but five, a dozen, 20 skillsets. That’s formidable. No lone prepper, no matter how well-armed and fortified, is resilient to all disasters. A group of people, able to depend on one another, is much more likely to survive.

The way to go about building this community if you don’t have one at hand is not to proselytize about the big issues (lest you fall into doom-related inaction, or simply scare someone off) but instead to focus on the small stuff. COVID-19 has provided a very practical reason for discussing prepping in loose terms. Have any of your friends stocked up on toilet paper, food, medicine? Are they careful when they go out to the store? What if we started stocking up for eventualities instead of disasters-in-progress? (And then you give them the bashful eyes and hands emojis.)

If your people are already on this wavelength, here is a useful tool for mapping out who can do what in your group. Start small, establish your skills and needs, and build out from there.

Preparedness is a journey. So long as we’re walking in that direction, we’re probably better off than we were the day before. It’s important to recognize that.

I know that this newsletter is a lot. I said some controversial things about our ability to fight climate change, and my tack is pretty dour in a subject that demands a guarded optimism. I don’t say these things from raw opinion, though. I’m by no means a climate scientist, but I am fairly knowledgeable on the subject and I cite my sources. I would love to be wrong—I’d love to have spent this time in error and for things to turn out rosy. I’ll take the L if it means we get to continue as a species.

But even if the truth lies somewhere in between my estimate and Elon Musk’s Yonic Carbon Extractor (he’d do that, you know. He’d make it some outlandish shape or give it a dumb name), it means dark times are ahead of us. The marker of 2020 should stand as a reminder of all the things we survived, and all the things that we can expect to come. I don’t write these newsletters because I want to ruin your day—I write them so that we all might be a little better off when things go wrong. I hope that you’ll join me in that journey, and that we can help each other along the way.